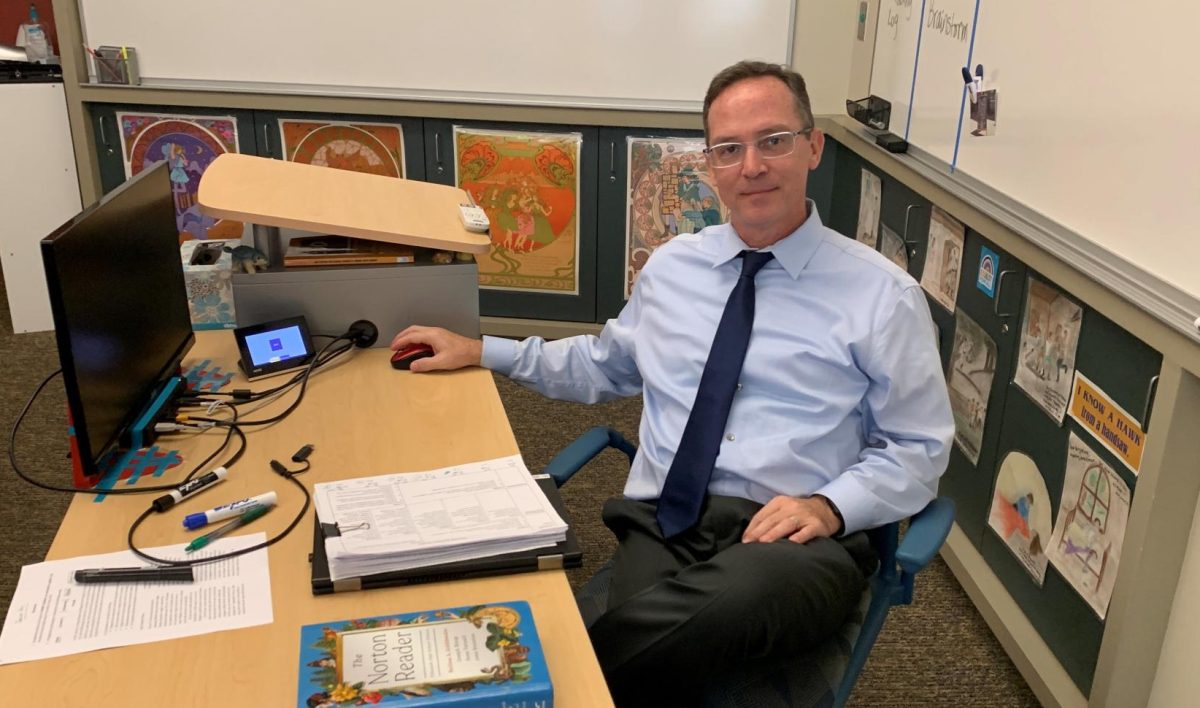

New to the English Department last year, Teacher Brian O’Connor helps students become better writers, but he also urges students to embrace mistakes in exchange for growth and development. He disagrees with the viewpoint of grades equaling success and believes a strict focus on results inhibits student’s improvement.

Below are some excerpts from the interview:

When and why did you decide you wanted to be a teacher?

My mother was an English teacher for a portion of her professional life, and she always spoke highly of the experience. I suppose her comments left an impression on me because I decided to go into education during my sophomore or junior year of college.

What is your least favorite part of teaching?

I guess it’s the living and working bell-to-bell. When your work life is divided into several periods and there is always a good reason to watch the clock, it can make a person feel rushed, underprepared, and tense. Most careers are not organized around six or seven periods throughout the day. I could be wrong, but I suspect other professionals do not feel as rushed as I sometimes feel.

What is your favorite part of teaching?

Teaching is more of a lifestyle than a “job.” A teacher gets to teach for nine or ten months, try some new strategies and make some mistakes. Then a teacher gets to go home for the summer and re-evaluate. What worked? What didn’t? What needs to change? How might it be better?

Most professionals do not get extended periods of time for reflection like educators do. The chance to reflect and improve is what I enjoy most about teaching.

Is there anything distinctive about Marist students?

Generally speaking, Marist students are too hard on themselves—academically. I believe one of the great misconceptions about grades is that they somehow magically determine future success, and Marist students, like many students in private schools, seem to buy into that notion.

I can also say that Marist students enjoy a certain camaraderie you don’t find in many school settings. The “Marist Fam” mentality appears entirely genuine, and that’s one aspect that makes this school distinctive.

What is the most influential text in your life?

That’s a tough question for an English teacher.

One book I find myself returning to on a regular basis is the book Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire. Freire is a Brazilian thinker and educator. I read the book years ago when cycling across Georgia, and it left a strong impression on me—as a teacher, thinker, and as a person.

If one word could describe who you want to be as a teacher, what would it be?

Approachable. At least I hope so.

Why did you decide to teach English?

I have a knack for English, unlike other areas like science or math or theology.

If you could write and investigate about one topic, what would it be? And where would you go?

I play this game where I imagine a book that I might write someday.

One subject that interests me, a topic that I think has not been thoroughly explored yet, are the Atlanta child murders that happened in the early 80s. I was in elementary school in Decatur at the time. I even went to school with a cousin of one of the victims. Writing a book about those murders and the trail of Wayne Williams that followed would make for a fascinating read.

Talking with Mr. O’Connor helped me to gain an understanding of who he is as a person and allowed me to see him from a different perspective. His advice to learn from our mistakes instead of dwelling on them will definitely help me in the future.

In order to make the most out of our Marist experience, we must get to know who our teachers are in and out of the classroom. Understanding our teachers’ outlook on certain subjects can give everyone a new perspective and outlet to discuss different topics.

If we can build a closer relationship with our teachers, we can better engage in classes and understand more material. There are numerous ways to get to know your teachers; you should take advantage of tutorial and class time to have meaningful conversations with people who help guide us everyday.